E. Nadine Isaacs Memorial Lecture

Bruce Golding

May 12, 2022

Allow me, first, to commend the Phillip and Christine Gore Foundation for its faithfulness in honouring each year the memory of a trailblazer in the conceptualization of housing solutions for the underserved population of Jamaica. Those of us who knew Nadine Isaacs and who, like me, had the privilege of working closely with her cannot fail to recognize and appreciate the sterling contribution she made not only in tackling our housing challenges but also in the advancement of the study of architecture to enhance our professional and institutional capacity to confront those challenges.

Nadine’s legacy

Nadine was persistent in her advocacy for the establishment of an appropriately accredited school of architecture in Jamaica to enable us to train our own architects as we were doing in respect of doctors and lawyers. That dream was realized in 1988 with the establishment of the Caribbean School of Architecture to serve not just Jamaica but all the small island states of the Caribbean with their peculiar sociological characteristics and environmental vulnerabilities. Quite fittingly, she subsequently served as head of the school.

Nadine was also strident in her quest for a legal framework to govern the practice of architecture – again, as had long existed in respect of other professions. I was pleased to have taken through Parliament in 1987 the Bill for the Architects Registration Act and just as pleased that she was chosen as the vice-chairman of the initial Architects Registration Board.

I am, therefore, honoured to have been asked to participate this year in this annual lecture series and to join with the Gore Foundation in invoking Nadine’s legacy in the continuing search for solutions to the housing needs of the majority of our population. I commend the Foundation, as well, for awarding a scholarship in the field of architecture each year in her memory. I congratulate the 18 scholars who have been chosen over the years. Nadine is not here to mentor you but she has left a template that will guide you to even greater achievements.

I remember Nadine so well – her diligence, the passion with which she engaged in discussing a project and the wealth of knowledge and research materials that she applied in finding ways to do new things or better ways to do old things.

The challenges we faced at the Ministry of Housing were not just to design houses and put them together. It was much, much more than that. The biggest challenge was the issue of affordability: designing projects and executing them in a way that would place the end product within the reach of the people for whom they were intended. Given the economic realities, what people could afford was virtually fixed and, therefore, the conceptualization, design and implementation had to be configured and tweaked to conform with that reality.

Yet – and Nadine was a stickler for this – there were minimum standards that could not be compromised in terms of safety, durability and functionality.

Nadine also understood very well that we were not just building houses but creating new communities – placing in closely contiguous spaces people who may have been complete strangers to each other – and she took into account a host of social factors that had to be appropriately weighted to ensure that what we were providing was not just houses but homes.

Invariably, the ends could not meet and the gap had to be closed by some form of government subsidy. This involved a trade-off: the deeper the subsidy, the fewer people would benefit. The less the subsidy, the fewer people would be able to purchase. Nadine was able to go beyond her professional discipline to provide useful guidance in calibrating that trade-off.

The difficult challenges that we faced then still confront us and the efforts to solve them continue. The realities today are as stark as they were then; indeed, as I will illustrate with research data, they are even more stark now than they were then.

The most recent iteration in 2019 of a national housing policy (I say “most recent” because there have been half-a-dozen or so such enunciations over the last 50 years but each of them has been able to achieve only a modest amount of its stated targets) illustrates how stark those realities are and it is instructive.

How our approach to housing evolved

But before delving into that, it is useful to review how the approaches taken to housing the population have evolved over the last 60 years. Indeed, we need to go back a bit further. 1951 is a good point of reference. Prior to that, people were largely expected to satisfy their own housing needs. The wealthy and the middle class did so effortlessly or with some sacrifice and effort. They owned or acquired land and they built structures that were commensurate with their means and their needs. The rural farming folk did so as well – much more modest structures made mostly of wood with detached toilet and kitchen facilities.

The migration of people from the rural areas to Kingston had led to the mushrooming of slum settlements along the Spanish Town Road corridor. As a result, the colonial government established in 1937 the Central Housing Authority which provided rental housing, tenement blocks of multi-family units, shared communal service areas and detached cottages. Bob Marley lived in one of those and remembered “when he used to sit in a government yard in Trench Town”.

1951 marked a turning point in our approach to housing. In August of that year, Hurricane Charlie – with about the same intensity as Hurricane Gilbert – struck Jamaica. Many of the houses, especially along the south of the island, the majority of which were made of wood, crudely constructed and never designed to withstand this type of onslaught, were totally destroyed.

The government’s response was to establish the Hurricane Housing Organization which provided materials and cash grants to assist people to rebuild their houses. Small core units were also built in places like Port Royal, Tower Hill and Balmagie. This marked the beginning of the government’s significant involvement in the provision of housing.

In 1955 the Hurricane Housing Organization and the Central Housing Authority were merged to form the Department of Housing and Social Welfare which, shortly after, was transformed into a new Ministry of Housing.

Government’s engagement took another significant step with the development of Mona Heights in 1958, Harbour View in 1960 and Duhaney Park in 1963. These involved a partnership between the government and the private sector with the government, in some instances, making lands available as well as providing a range of concessions and the private sector undertaking the design, construction and relevant infrastructure. This strategy was subsequently utilized on projects like Hughenden and Edgewater and Independence City. Initiatives like the Government Mortgage Insurance Scheme facilitated the development of housing projects like Hope Pastures, Trafalgar Park, Patrick City, Pembroke Hall, Ensom City, Drumblair, Havendale, and a number of others.

The Housing Act which was introduced in 1968 empowered the Minister of Housing to allow private developers to bypass the approval requirements of the planning authorities, fast-track their projects and save costs.

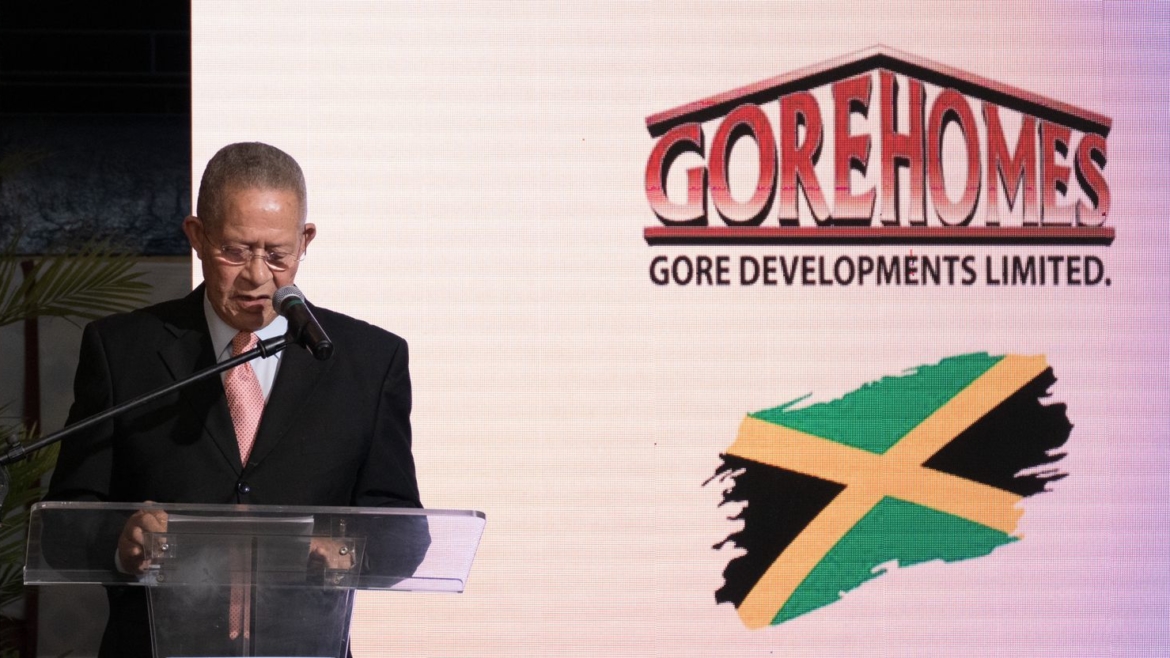

These projects did much to address the needs of the growing urban middle class, a segment of the market for which the private sector, operating alone or in partnership with the government, has amply demonstrated its capacity to satisfy. Gore Developments has been a stellar performer in this regard. It has been in existence for 50 of the last 60 years over which time it has built over 16,000 houses in 19 schemes across four parishes. It has been able to deliver these units at competitive prices by maximizing the economies of scale and its meticulous attention to coordinated planning and project management.

Appropriate housing for the lower income groups has, however, remained the big challenge. The limit to what they can afford makes this group unattractive to private developers and unbankable to private sector mortgage lenders. Their prospects of owning a home depend largely on the government.

Over these 60 years, the government has undertaken several projects targeting these groups not only in the Kingston Metropolitan area but in rural towns which have themselves become urbanized and to which much of the migration from deep rural communities has turned, given the increasing shortage of land and accommodation in the KMA. The advent of the National Housing Trust provided a valuable source of long-term mortgage financing to support these efforts.

Our persistent housing challenges

Two issues arise here. First, despite its best efforts, the number of government projects has never been able to meet the demand. Second, these projects were out of the reach of the two lowest quintiles. In other words, the housing needs of as much as 40 percent of the population were not being addressed.

This dilemma has been clearly acknowledged. In the Strategic Mandate Review of the NHT published in 2017, it says “The Commission recognizes that a clear imbalance exists between the nature, level and sustainability of income at the lower levels which impairs the ability to qualify for and service a loan over the medium to long term at the current level of house prices”. It was even more explicit. It disclosed that a survey of NHT contributors revealed that 26 per cent of them were in need of and desirous of a housing solution but only 7 per cent of them were earning enough to meet the monthly payments for the most basic offering – even with the subsidies and zero interest rate that it offers to this income group.

The sad reality is that the situation – the affordability gap – is not getting any better; it is getting worse! The rising cost of construction has been putting Usain-Bolt-like distance between itself and the incomes of the low-income population. The 2019 National Housing Policy provides data which makes this point tellingly. It uses the construction price index – part of the legacy of one of our most accomplished quantity surveyors, the late Brian Goldson, – to illustrate that in 1979 a minimum wage earner could afford to service a mortgage for a two-bedroom house. In 2016, it required 9 times the minimum wage to service a mortgage for that same two-bedroom unit. It is likely to be even worse now.

This reality is reinforced by data provided by the NHT (and, I must point out that this is based on 2014 figures). Forty-six per cent of its contributors earned less than $7,500 per week. Using the rule of thumb that what a person can sustainably afford to pay for housing should not exceed 30% of his income, a person at the top end of that scale, even with zero interest rate and no downpayment, would have been able to service a mortgage of no more than $4 million. In 2014, the cheapest house being offered by the NHT was around $8 million.

Over the years, a range of initiatives were introduced to address this problem. These include the provision of vacant lots with appropriate infrastructure (at various stages called Sites & Services or Serviced Lots) with the expectation that beneficiaries would find a way to erect their own houses. Another approach that was introduced was the provision of a small one-room core with the necessary plumbing and electrics (Starter Homes) – again with the expectation that the beneficiaries would find a way to expand it to meet their requirements and as their means allowed. More recently, Operation Pride was rolled out.

These have all been of benefit to some in the lower income groups but not only has the supply lagged far behind the demand but even these stripped-down solutions have proven to be unaffordable to a significant portion of the lower income groups.

Quantifying the problem

The different “editions” of the National Housing Policy over the years have sought to quantify the housing deficit and the number of houses that would be required each year over a specified period (usually 10 years) to erase the deficit as well as to replace houses that become obsolete. That magic number has grown over the years from 10,000 to 15,000, i.e. the number of housing units that would need to be built annually.

How has our performance stacked up? In the last 60 years, we have built a total of 221,000 houses or an average of just under 3,700 units per year. Seventy percent of those were provided by the public sector with the remaining 30 percent by the private sector which, I must point out, includes individuals at all income levels who build their own homes.

I am not here simply to paint a dismal picture but it is important to understand the dimensions and the dynamics of the problem. While there is no perfect solution, the problem does not have to overwhelm us.

We must start by acknowledging that the ability of people to buy a house is inextricably linked to how much they earn and the reliability with which they earn it. The unemployed who hustles every day, makes a thousand dollars today and a five hundred dollars tomorrow, is not going to be able sign a mortgage agreement and collect the keys to a house. We do him a disservice if we cause him to believe that he can.

So, what does he do? The one or two room house that he grew up in can’t accommodate him, his baby-mother and the two children. But they have to live somewhere. So he scouts out a piece of land somewhere that is convenient for his hustling. Most times, it is government land but it may well be private land that has not been visited by its owner for a long time. He puts down whatever he can put down – pieces of old lumber, some sheets of old zinc. He is providing himself with one of the basic necessities of life.

Over time, if the hustling gets better or he is fortunate to pick up a steady job, he lays some concrete blocks. He calls that “home improvement”. Over time, what started out as a “whappen-bappem” becomes a fairly decent two or three bedroom house. He has solved, to a considerable extent, his housing problem but he has no peace of mind because he has no way of knowing when the bulldozer or the court bailiff will turn up.

In the NHT’s Strategic Mandate Review of 2017, it is estimated that there are over 750 squatter settlements scattered across the island on which approximately 600,000 persons live. According to the 2019 National Housing Policy, most of these settlements have been in existence for more than 20 years. It is reasonable to assume that many of those persons who don’t qualify to buy an NHT house because they are at the bottom end of the affordability gap can be found there.

We agonize and we make pronouncements about the incidence of squatting. But let’s not fool ourselves. Squatting will not stop until we find a way to address the shelter needs of that hustler who has to find somewhere to put his baby-mother and the two “youth”, somewhere where they can sleep at night.

So what do we do? Let’s recognize some basics.

In that hustler is an energy and determination that we must not overlook. It takes energy and determination to do what he has done. It is illegal and misplaced but he will argue – and quite persuasively – that he had no alternative. For, what alternative can we suggest? What we might do is to harness and channel that energy and that determination into an effort that is not illegal and not misplaced.

I share with you an anecdote that effectively illustrates the point.

At the Ministry of Housing back in the 1980s, we faced a serious squatting problem in the Montego Bay area. With the rapid growth in tourism, people from almost every parish were descending on Montego Bay in droves hoping to find a job or get into some good hustling. We identified 100 acres of land in the Rose Heights area on which we intended to build 600 houses to help to alleviate the problem. It took four or five months for the title to be transferred and I visited the site with the technical officers (Nadine may well have been among them) to see how the project would be set down. When we got there, we could hardly find a square of land that had not been pegged out by people, some of whom had already started to build. We subsequently decided to convert it into a settlement upgrading project by putting in the necessary infrastructure – roads, water, drainage etc., regularizing the occupants and giving each of them a title. Go there now and you would be amazed at the quality of houses that many of them have, over time, been able to build.

I want to offer a few suggestions.

I disagree fundamentally with those who suggest that we should abolish the NHT, convert the contributions into a tax and use those funds to boost expenditure in other, albeit critical and underfunded areas, like education and health services. It is well and good to argue that if people are educated and healthy, they will be able to take care of their own housing needs but that would be a long time in coming and children are not likely to be educated and healthy if they have nowhere to live.

I regret that between 2013 and 2025, some $145 billion will have had to be diverted from the NHT, initially to support our fiscal consolidation programme and subsequently to make up the revenue loss caused by COVID. I understand the important reasons why it was done but, as I have said repeatedly, it constitutes a flagrant breach of the trust on which the NHT was established in 1976. I had suggested that, in return, the government transfer lands suitable for housing to the Trust of equivalent value so that, ultimately, contributors would not be deprived of the benefits to which they are entitled.

Be that as it may, the NHT must continue its efforts to fulfill the dream of its contributors to own a home. It will continue to be bedeviled by the fact that almost a half of its contributors are unable to afford even its most basic unit. The Strategic Mandate Review points out that the conversion rate, i.e., the percentage of contributors who are able to obtain mortgage benefits, is 32% for the top 44% of contributors but only 14% for the bottom 56%.

Government’s revised/renewed housing policy directions

All is not lost. The NHT’s Strategic Management Review has put forward several recommendations to realign its offerings to more equitably address the needs of its contributors. The 2019 National Housing Policy document provides a comprehensive analysis of the housing problems and sets out the policy directions to address them which, commendable though they are, are as over-ambitious as the previous versions. Time could never permit me to review them here in detail. I offer, instead, some thoughts on the general approach that I think should be taken that are not inconsistent with what is outlined in those two documents but which need to be more targeted and strategically managed in terms of the identification of projects and beneficiaries and the allocation of resources. That approach must be tailored not just to the needs of the underserved population but to their economic circumstances – what they can afford because that is what will be doable.

It must also take carefully into account the fact that many in the underserved cohort operate in the informal economy where incomes fluctuate. Mortgage payments may not be possible on a fixed monthly basis but must be flexible enough to be allowed to level out over three or four months.

The private sector should continue to be relied on and should be encouraged and facilitated to be the primary provider of housing solutions for the middle-income segment of the market (and by “middle-income”, I’m suggesting those with a net disposable income of more than, say, $70,000 per week). More can be done to eliminate costly and frustrating bottlenecks in the planning and approval process.

I note – and it is a welcome development – that with the trending down of interest rates, private sector mortgage lenders like the building societies and insurance companies are making more funds available – over $30 billion last year – for mortgage lending.

I believe that projects like the NHT’s Ruthven Towers with unit prices averaging over $30 million should have been left to private sector developers. Not that the NHT should not finance mortgages for that type of project because eligible purchasers are among its contributors and they are entitled to receive mortgage benefits like any other contributor, but the time and effort it spent on Ruthven Towers would have been better spent delivering housing solutions to its underserved cohort.

We must carefully identify and give appropriate weight and priority to the range of solutions that are needed to address the range of circumstances of the underserved housing market.

The NHT’s Strategic Mandate Review indicates, based on a housing demand survey that it conducted, that there was a need for (and it was very specific) 105,172 housing solutions but only 31,229 of those would take the form of fully built housing units. The other 73,943 (70%) could not afford a fully built house but would require some other form of intervention. This data is most instructive.

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel to find appropriate solutions. I can hardly think of any approach to low income housing that we have not tried at some stage. The archives of the Ministry of Housing, wherever that is now domiciled, is filled with records of programmes on which we embarked – some at great expense and with much fanfare – only to abandon them and turn to something else. Yes, we made mistakes but it is sometimes foolhardy, instead of learning from our mistakes and getting it right, to entirely discard an approach and embark on a new one, very often, only to make the same mistakes again. We have lacked focus and steadfastness.

Part of our problem is that the issue of the provision of housing has been weaponized. We pontificate from the political platforms about who has provided more housing solutions when, in fact, none of us has provided anywhere near enough.

We have gathered enough data and, with a little more analysis, we are in a position to determine what solution best fits whom:

- Is it a finished 1 or 2 bedroom unit, the mortgage for which the beneficiary is in a financial position to service?

- Is it a mortgage loan for those who have access to land to be able to build a house on that land?

- Is it a serviced lot for those who can find the means, perhaps incrementally over time, to build something for themselves?

- Does that serviced lot have to have paved roads, kerb walls and sewage plants or can we treat the infrastructure requirements also on an incremental basis?

- Is it to treat a squatter settlement as a de facto housing scheme that needs to be fixed and upgraded?

Land ownership is an emotional issue in Jamaica. It is also the starting point in owning a home. The government is the biggest landowner in Jamaica – over half million acres. Some of those lands are prime agricultural, some valuable for resort and commercial purposes, some are essential for expansion of our congested cities and towns. But much of it is idle and offers little or no immediate economic potential.

Land and empowerment in housing solutions

Let’s suppose we were to embark on a serious programme of identifying suitable parcels of government lands and say to the hustler “Don’t go capture a piece of land over there and squat; come and sign up over here. We will mark out your lot and prepare your title; we will cut the road, put in the drainage and water pipes. It may not be asphalted roads, it won’t have any kerb walls but this is where you can put whatever structure you were going to put on the captured land.

There are issues that would have to be addressed to make this work. Some of the current onerous requirements for subdivision approval and the issuing of titles would have to be modified – significantly modified. The planning authorities who believe that the economic circumstances of our low-income people must catch up with their orthodoxies will have to be brought in line. The argument that what we would be doing is simply legitimizing slums would have to confront the reality that the slums are being created before our very eyes and in a disordered manner that makes them difficult to retrofit.

We would have to contend with the resistance of the local authorities who fear that once people are placed on land without elborate infrastructure, they are going to come under pressure to provide it.

We would have to be prepared to make the land available at below-market value so that the bulk of the mortgage that the beneficiary would have to repay would be for the cost of surveying, titling and basic infrastructure.

I know some will say it is bad policy to give away government land. What else are we to do with it? Let it remain idle…in ruinate while a third of the population can’t find somewhere to live? It has no fiscal value so it doesn’t place any burden on the budget. We provide incentives for manufacturers, exporters, those in the tourism sector, BPO operators. What can be wrong in incentivizing the low income earners in a way that will have the greatest impact on their lives and future?

We are not – not now and hardly ever – going to be able to provide a house for everybody regardless of their means….not with cement at $1350 per bag, ½” steel at $2100 per length and $5,650 for a 10-ft sheet of zinc.

But if we were to ensure that that hustler, that street vendor, that gardener or domestic helper and people like them have a piece of land – that pegged out lot – many of them would get busy and start building right away. Many would do it incrementally….start with the “whappen-bappem” they can afford and then upgrade to the block and steel when they can manage that.

One of the amazing things that I discovered at the Ministry of Housing and which Nadine so often pointed out is not just the resourcefulness of our people but the access they seemed to have to resources that no mortgage lender would ever able to quantify or put down on paper. A person who received a Sites & Services lot often had a brother or a cousin or a friend who was a mason or carpenter who helped them to build something. Some had relatives abroad who would send money to help them build something. Some got help from their church. It was hardly ever easy but they were able to put a roof over their heads.

Some of them may never manage to build anything; their economic circumstances may just not allow. But in years to come their children may be able to do what they were not able to do. Appropriate caveats could be imposed to prevent such a programme from being captured by speculators.

Squatter settlements – a symptom as well as a potential solution

And what do we do with the 600,000 persons living on squatted lands all over the country? Driving them off the land is out of the question. What they have built on the land, however modest it is, however unsightly it may appear represents capital investment….considerable capital investment. Do we dare put a bulldozer to that? And what capacity do we have to replace it?

There are those who will say that anything short of removal is giving permanence to a serious threat to the environment. I submit that the greatest threat to the environment is poverty and squatting is merely a manifestation of that poverty.

Some of these squatter settlements can be regularized through infrastructure upgrading, surveying and individual title registration. Mortgages can be tailored to meet the costs incurred.

Some of these squatters will have to be relocated, especially those on lands vulnerable to hazards, lands that are privately owned or lands where they have settled in such a haphazard way that infrastructure upgrading is too difficult or costly.

It is through this structured, coordinated approach that many low-income earners, including those unqualified NHT contributors, would be able to meet the requirements – not for an $8 million mortgage but for a $600,000 loan to buy some blocks and steel and cement and zinc sheets to build the little one room and bathroom or transform the “whampen-bappem” into something more elaborate.

Financing housing solutions

How would we finance this? The NHT is the primary source of mortgage lending, especially for low-income earners. Its lending was intended to be restricted to its contributors – much like a thrift society. Much to my chagrin, that solemn obligation has in the past been breached with funds being diverted to provide housing to non-contributors in inner-city communities.

I take that solemn obligation seriously. But the inflows to the NHT are robust enough to allow some leveraging to finance solutions for non-contributors. The NHT pulls in each year around $30 billion of mandatory contributions (net of refunds). Especially after the annual drawdowns for budgetary support come to an end in 2025 (and I pray God it does not go beyond that), some NHT funds could be leveraged with an appropriate guarantee and treated as an investment no different from the range of instruments in which the NHT normally invests in order to finance housing solutions to those low-income earners who are not NHT contributors. The repayments would return the funds to the Trust.

The Prime Minister announced some years ago that the government was devising an institutional framework for a secondary mortgage market. That was the primary mandate of the Jamaica Mortgage Bank that was established more than 50 years ago. During much of that period, the financial environment was not friendly to secondary market activity. Secured mortgages, however, are an attractive investment for long-term institutional investors like pension funds and insurance portfolios. In our current improved financial environment, it could be a means of increasing the flow of funds to finance housing solutions.

Yes, we must continue to provide the $16M and $17M two-bedroom house for those whose incomes can afford it – the teachers, nurses, mid-level managers, supervisors and technicians. We must encourage Phillip and Chris Gore and others like them to continue to produce the quality houses they are building which have brought so much satisfaction and made such a difference to the wellbeing of the thousands of their purchasers. Yes, we must salute and encourage Food for the Poor to continue to provide their modest but oh so welcome houses for those who are living in squalor and are unable on their own to do otherwise.

But let us take some bold steps – not necessarily thinking out of the box because we have been sitting in that box with its stark realities for many years – to put the unserved and underserved population on a path to achieve one of their most earnest desires: having somewhere to live, somewhere they can call their own, somewhere they can raise their families and try to better their lives. And, importantly, something that enables them to acquire wealth so that if they seek a small business loan to step up in life, the security they are able to offer is more than the shirt on their backs and the cellphone in their pockets.

It is more than just a means of addressing the housing crisis that afflicts a large portion of our population. To use a kackneyed word, it is empowerment…..enabling our people to own a piece of this rock that should be their birthright. Let us empower.